When it comes to wine, the consensus is that you should drink the wines that make you happy. At the end of the day, quality, style, price and recommendations from the finest of sommeliers mean very little if that wine just doesn’t work for you. To each his own. In terms of steaks, this logic applies as well, not that it has prevented the debate over to which point a steak must be grilled to rage on endlessly. I’m not here to solve that debate – but perhaps to give my take on it.

One of the fun but essentially non-transferable skills that you pick up from working in a steakhouse is being able to 1) guess pretty accurately how people like their beef cooked and 2) and to which point a steak has been cooked by glancing at it. But first let’s review the various grilling points that any steakhouse should be able to hit. The scale, running from faintly mooing to burnt to a crisp, goes likes this:

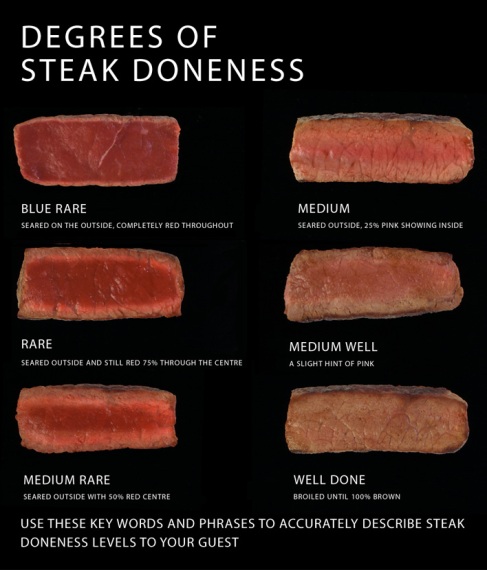

Blue – Rare – Medium Rare – Medium – Medium Well – Well Done. Below is an illustrative chart explaining their differences. A key point to remember that beef cooked Blue and Rare is never served cold – it has to be hot but the meat can’t have been cooked through.

Now, at least in London, 60% of clients ordered Medium Rare, another 30% were split evenly between Rare and Medium Well and the remaining 10% spread randomly around Blue, Well Done and Very Well Done. In Argentina, the numbers are closer to 70% Medium another 20% ask for Well Done and only the odd lunatic goes for Medium Rare or less. More on this later.

Anyways, given the rates that we were seeing in London, we would take notice when someone asked for a Rare steak. Some announced their choice bravely and loudly, as if they deserved a gold star having the courage to order a steak Rare. Almost everybody asking for Well Done or Very Well Done apologised for their preference, much like when non-smokers apologise for not having a lighter on them when asked. French tourists made up the 70% of steaks ordered Blue and most people ordering the smallest steaks also ordered them more cooked. And believe it or not, peer pressure exists when it comes to grilling points. I can’t understand why, but in many groups of friends there’s always one self-appointed grilling point supervisor who will cluck disapprovingly if anybody orders a steak beyond an arbitrarily determined point. The most interesting part though was when I was asked what I recommended as grilling points. The story of to each his own also applies here but it’s true that nature of the cuts matters when choosing grilling points. For the larger Bife de Chorizo I didn’t recommend anybody doubting of their choice that they go with Rare just because it is so large and that is a large amount of relatively uncooked beef to get through. I also think Medium Rare works a bit better on cuts that are fattier because the extended heat helps to breakdown the marbling better. So, Bife de Lomo Rare or Blue? Right on, but not the Ojo de Bife if you aren’t already sure you like it that way.

The debate about grilling points really verges on the fact that those who prefer it less cooked insist that by extending the cooking the meat loses its juices and tenderness and becomes irremediably inedible. The opposing camp usually can’t bear the thought of blood and juices pooling in their plate. Each has a point. In Argentina the standard is not only to grill the meat to at least Medium, but that at asados you don’t get to pick the grilling point. As the pieces are grilled whole and it is up to the asador when the cut is ready, you best like whatever is served to you. It isn’t entirely clear to me why in Argentina everybody also prefers their beef grilled longer. My working theory is that the quality of the beef is such that even if you get it Well Done it is still tender and tasty. But there’s basically no science or method behind that statement so take it a considerable amount of sal parrillera.

I personally go for a Medium Rare and on occasion will ask for a Rare. Amongst friends I won’t blink if the beef is Medium. When the wine is good and the company better, I’m not sure that it matters all that much to me as long as it’s been done Argentine-style over a parrilla!