In terms of eating there is a lot left to personal preference. This can be attributed to many factors including, palette inclinations, what kind of food you grew up with or simply how hungry you are at a specific point in time. The same applies for beef. Cows are huge and when butchered they produce a lot of different cuts. If you will indulge me, in the next few paragraphs I’d like to take the opportunity to better acquaint you with some of the more popular cuts of steak.

So for starters, what is a steak? Yeah, obviously it’s meat but what is it that qualifies a cut of meat as a steak? In the most general way a steak is a piece of meat that can be classified as something “fast-cooking”. What this means is that the beef itself is low enough in connective tissue that an extended amount of cooking time isn’t necessary. The biggest difference between a steak and a roast really is the size.

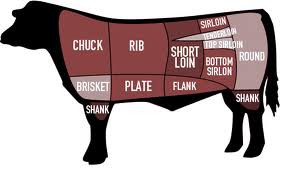

It’s true that the cheaper cuts such as skirt steak, flank steak and sirloin are becoming increasingly popular these days. However, some the best cuts are still coming from the Longissimus dorsi and the Psoas major. The tenderness of a steak is inversely related to how much work a muscle does during a cow’s lifetime. The two previously mentioned muscles are extremely tender which makes them ideal candidates for a delicious steak. From these two large cuts come a number of other smaller cuts that you’d find at any typical butcher shop.

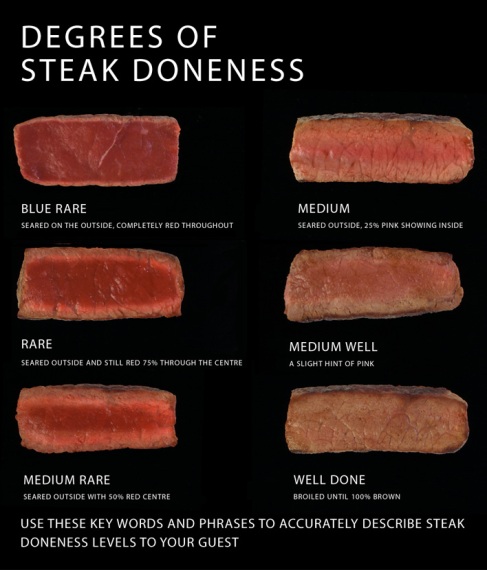

Let’s start with the Ribeye, a cut from the front end of the Longissimus dorsi. This is a highly marbled piece of meat with a large swath of fat separating the Longissiumus from the Spinalis. With beef, fat is where the distinctive flavor comes from. Because of this ribeye is one of the richest cuts out there. When it comes to cooking this tasty slab grilling, pan-frying and broiling are your best bets.

Now onto the New York Strip steak. This cut comes from the rear-end of Longissimus dorsi muscle just behind the ribs. It is moderately tender with good marbling and an intense beefy flavor. This is by far one of the favorites in all steakhouses. This cut is easy to grill because it has less fat and therefore causes less flareups. You can also pan-fry or broil it although obviously in terms of Argentine Asado this wouldn’t be acceptable let alone ideal.

The Tenderloin sold as Filet or filet mignon is cut from the central section of the Psoas major muscle. It is an extremely tender piece of beef with a buttery texture. It’s low in fat and because of this it is also relatively low in flavor. The tenderloin tends to cook much faster than other cuts because it is so low in fat. Pan-frying in oil and then basting it in butter is a common method of cooking because it adds some richness to this meat, which is prone to drying out. Another popular method of cooking a filet mignon is to wrap it in bacon. It’s essentially the same idea as the butter in that it helps to add some richness in flavor.

Another extremely popular cut we have is the T-Bone steak known as a porterhouse. What’s cool about the T-bone is that you’re getting two different cuts in one. It’s comprised of a piece of strip as well as a piece of tenderloin that’s separated by a T-shaped bone. It comes from the front end of the short line. Grilling is hands down the best method to cook this steak. The only thing to be mindful of is overcooking the tenderloin before the piece of strip is done. What is so convenient about grilling it is that you can control what section of the meat is near the hotter end of the grill.